Each year, to honor Breast Cancer Awareness Month, the Comprehensive Breast Program at Dartmouth Cancer Center holds a breast health education event. Participants have the chance to submit questions to a panel of medical experts. At the last event, the most common question was about breast density: what does it mean to have “dense breasts,” and what is the connection between breast density and cancer?

General Surgery advanced nurse practitioner Carol Huntley-Smith, APRN, was at the event to answer the question. It’s one she gets a lot. She frequently works with breast cancer patients at Dartmouth Cancer Center, Keene, and people with concerns such as a breast lump or family history of breast cancer. She answers the question by having conversations with patients about breast anatomy and how breast density is determined.

In basic terms, she explains that breast tissue is composed of lobules (which produce milk), ducts (which deliver milk to the nipples), “fibroglandular” or fibrous tissue (which gives breasts their structure and shape), and fat (which fills the remaining space). “It’s normal for breasts to feel lumpy and bumpy, but breast density isn't determined by how breasts feel or look,” Huntley-Smith says. “Instead, it's a measurement made by a radiologist based on the ratio of fibroglandular tissue to fat in your breast tissue as seen on a mammogram.”

Breast density levels

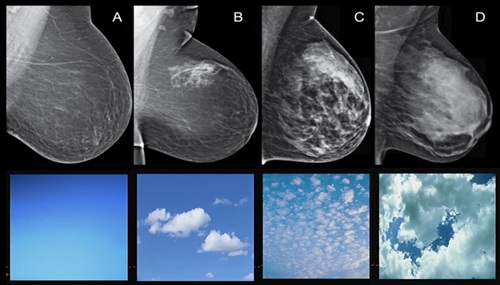

Huntley-Smith explains that there are four levels of breast density, with two categorized as dense and two as non-dense:

- Extremely Dense (Category D): This is the highest density category, with breast tissue that is mostly fibroglandular. Approximately 10 percent of women fall into this category.

- Heterogeneously Dense (Category C): This category has more fibrous than fatty tissue. About 40 percent of women have heterogeneously dense breasts.

- Scattered Fibroglandular Density (Category B): The ratio is slightly more fibrous than fatty in this category. About 40 percent of women fall into this category.

- Mainly Fatty (Category A): This is the least dense category, where the breasts appear darkest on a mammogram, making it easier for radiologists to detect abnormalities.

Breast density and mammograms

As far as imaging goes, mammograms are the most effective way to detect breast cancer, and what radiologists and the Society of Breast Imaging recommend annually. However, increased breast density can make it more difficult for radiologists to accurately interpret mammograms.

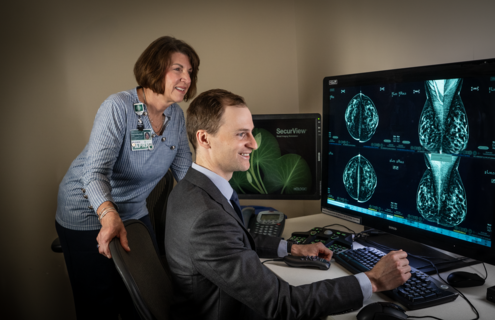

Radiologists play a crucial role in the full spectrum of breast cancer care. Their work includes reviewing screening mammograms, calling patients back for additional evaluations, performing targeted ultrasounds, and reading breast MRIs. They also perform biopsies and collaborate with surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists to ensure that all imaging is coming together for patients who do have breast cancer.

Dartmouth Health Radiologist Mark W. Johnson, MD, MMS, specializes in reading mammograms. He also attended the event to explain why dense breasts are difficult to read on a mammogram report: fibroglandular tissue of dense breasts appears white on a mammogram, and cancer also appears white. This can make it challenging for radiologists to spot potentially concerning white areas, such as tumors, against the white background of dense breast tissue.

“We know that with increasing density there is an increasing risk of breast cancer,” Johnson says. “And it also goes along with a decreased sensitivity of mammography.” This means that in dense breasts, there's a slightly higher chance that a mammogram might miss something.

Supplemental screening options

Because of the challenges in screening dense breasts, supplemental screening may be recommended in addition to mammograms. Supplemental screening currently available at Dartmouth Health includes:

- Breast MRI: For individuals at high risk of breast cancer, a full breast MRI may be recommended. MRI is more sensitive than a mammogram and can often detect abnormalities at an earlier stage. However, full breast MRIs are costly, and insurance coverage can be a challenge.

- Abbreviated Breast MRI: To address the cost issue, a shorter version of the full MRI is offered to those who have no significant risk factors for breast cancer other than heterogeneously or extremely dense breast tissue. Huntley-Smith says because an MRI is so sensitive, this abbreviated version is “still really good at picking up breast cancer that a mammogram may miss and is more affordable than a full MRI.” While insurance coverage is improving, abbreviated breast MRI may not always be covered. At this time, in 2025, the scan may result in an out-of-pocket cost of around $400.

Which type of screening do you need?

In September 2024, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) started requiring all mammogram reports sent to patients to include breast density, which should be described as either “not dense” or “dense.”

In addition, providers sometimes use risk models like the Tyrer-Cuzick risk model, which incorporates breast density along with other factors to calculate an individual's risk of breast cancer. Based on the risk assessment, recommendations for screening and follow-up are made.

“For patients with no family history, whose own risk of breast cancer is less than 15 percent, typically an annual screening mammogram is suggested,” Johnson says. “Patients at 15-20 percent risk are in an intermediate zone. Because there may be insurance challenges with getting a breast MRI paid for, we offer supplemental screening with abbreviated MRI, which has pretty much the same sensitivity and specificity as a full breast MRI. Patients who are greater than 20 percent are in a higher risk category. We may follow these patients with mammography alternating with MRI every 6 months.” Decisions around breast cancer screening frequency and type are individual and are best discussed with your primary care provider.

Learn more

Understanding breast density is crucial for breast health and early detection when cancer is most treatable. “Get comfortable with what your own breasts look like and feel like so that if there is a change, you can tell somebody,” says Huntley-Smith.

The American Cancer Society offers an excellent guide to understanding breast density and mammograms. For personal questions about your breast density or risk of breast cancer, talk with your primary care provider or a breast specialist.